Guest Blog: Ethics

Thank you to Stuart Grey for this Guest Blog. Stuart is a Research Associate at 'VR: Immersive Documentary Encounters' & was the only academic partner on the collaboration to have some time secured with funding from EPSRC. He was a brilliant lynchpin in the whole endeavour, keeping us on time & to task with unflagging enthusiasm.

The process of university ethics can be complex and time consuming in the UK. The most common process followed by UK universities begins by answering a series of key questions about your research project. For example, “am I collecting any personally identifiable information about my participants?” or “am I working with children, animals, or any vulnerable groups?”. If the answer to one or more of these types of questions is “yes”, then your research project must undergo further and independent scrutiny and this additional ratification requires much more time and planning on behalf of the applicant.

For universities, this usually entails a formal ethics proposal which details the specific activities which will be undertaken, the process of obtaining informed and continued consent, how data will be captured and later be protected. This application must be completed in the weeks and months prior to actually carrying out the research, to ensure that it is reviewed fairly and thoroughly. At the University of Bristol, it can take anywhere from 2 weeks to 4 weeks for the Faculty of Engineering ethics committee to approve a submission depending on the numbers of concurrent applications under review and the complexity of the project. Yet, this due diligence is incredibly important. It helps to safeguard our participants and staff members from harm, as well as the reputation of the institution. And while for external partners this process can feel frustrating, it is important to reflect upon the fact that it is the University’s reputation for ethical research which gives our participants the confidence to involve themselves in our projects, which they may not otherwise be willing to do.

In the collaboration between the University of Bristol, Kilter and our partner school, there were various ethical concerns to control for. Perhaps the greatest concern was that around contact with school children. Ideally all team members who attended the school would have had active Disclosure and Barring Service (DBS) certification, however, we could not guarantee this for our project as some team member’s accreditation had expired. In our ethics application then, we stipulated that at least one team member with active DBS certification would be present at all workshops, that no team members would have individually unsupervised interactions with children during the workshops, and that a member of the school staff would be present at all times.

Data privacy frequently results in ethical consternation for researchers, ethics committees, and now, subsequent of a series of shocking public scandals, for participants themselves. With this in mind, as researchers, we live by the following mantra, “only collect data which you need and never collect data without a predefined reason for doing so”. Adhering to this decreases the risks posed to participants and assuages the nerves of researchers and ethics committees alike. Hence, in our project we had to consider just what exactly we needed to know about our participants. Moreover, we also had to make provisions for its safe storage.

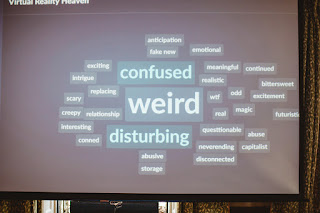

When it comes to VR, however, there are also some nuanced ethical considerations. For a technology with the power to truly immerse users, it is important to consider the psychological risks presented by the content we are providing users with. Yet, as defined by the goals of the project itself, there are no unified positions on exactly which types of VR experiences pose psychological risks. Hence, for an ethics focused workshop, we had to balance showcasing new users with the immersive abilities of VR in order for them to understand the potential power of this technology, with ensuring that the content shown would not have any adverse effects upon them.

As well as ethical concerns to assuage within the practicalities of undertaking research with school children, as researchers, it is also important to consider your own ethical principles - concerns which may not necessarily hinder your ethics proposal but which reflect the core mission of the project. In our case we wanted to empower children of different genders, ages, and interests to collaborate and project their visions of the future. Rather than simply crowdsource their ideas, we wished to grant them a platform to have their voices about VR ethics heard by those in a position to affect the direction of the technology. In this way, undertaking research with children is as much about how we can empower them rather than simply about what we can get from them.

Comments

Post a Comment