Guest Blog: Schools Workshops Blow by Blow.

Thanks again to Stuart Gray for providing this insightful detail into the VR Workshops we ran together at Redland Green school in Bristol

VR Workshop 1 - Thinking About the Future

We arrived at Redland Green School just after lunchtime on a bright and unseasonably warm Wednesday in late February. This was to be the first of six workshops exploring the ethics of VR and Quantum technologies with young people, as part of the school's ‘Enrichment Programme’ - a programme which supported the development of pupil’s skills beyond the scope of the regular curriculum. The first three sessions would focus on VR; our crew comprising Olly and Caroline from Kilter - who would be leading proceedings - as well as Stu and Chris - VR researchers from the Centre for Innovation and Entrepreneurship, who were involved in co-developing the sessions, and would play a supporting role in both facilitation and data collection.

The first workshop started with a little confusion due to issues surrounding the project consent forms. We had distributed the consent forms in the weeks prior to the sessions but, as can be a common occurrence in the exchange of permission documents between home and school contexts, not all of the twelve Year 9 and 10 pupils involved had confirmed their consent prior to the first workshop. This had led us to make an anxious phone call in the week of the first workshop to the school to request a reminder be sent to the remaining pupils to submit their forms. On the day of the first workshop, we were nervous as to what would happen if some of our attendees would be unable to confirm the consent of themselves and their parents in writing. What would we do? Could we ask the pupils who had not confirmed their consent to go to the library? Was that even fair? We decided that if more than 30% of the class had neglected to confirm their consent, we would run the session without collecting any data.

Fortunately for us, as the pupils bounded into the classroom still riding high on their lunch break sustenance, several of them were proudly brandishing their consent forms in hand. Scanning the classroom and doing some quick mental maths, it seemed as if we were in the clear - the freshly submitted forms supplementing those of our better-organised participants. A lesson learned for any researcher working in school contexts - never underestimate the powers of persuasion senior teachers can have in motivating the return of permission slips!

After these early inconveniences were resolved, our first workshop progressed well. The pupils appeared eager and inquisitive with regards to our planned adventure together. Several asked questions before the official introduction had been given, “I’m really interested in VR gaming and being able to develop VR apps myself” said one enthusiastic pupil. At this point, some of us felt a little concerned. Had we been clear enough about what the workshops would entail when we had sent the pupils and their parents an information sheet about the project? Had we oversold the skills we would be equipping them with as part of the process. “You and Chris should have a lot to talk about. He develops VR applications,” Stu responded in an attempt to pre-empt any latent disappointment he may have been about to experience. Over the remaining workshops, it seemed to work and he had plenty of technical questions for Chris and Stu over which to supplement his enthusiasm for the ethical discussions.

It had been an unofficial objective for the team to empower a range of different perspectives within our workshop process, as a creative strategy as much as it was a moral virtue. We didn’t just want the “tech geeks”, neither did we just want the “artists”. That would’ve been too easy and may have led to ‘group think’. We knew, as a team involved in interdisciplinary collaboration, that sometimes the greatest creative innovations can be garnered from the friction between different or competing ideas, world views, and expertise. With this in mind, the workshops were designed to foster a cacophony of different voices, by involving pupils of mixed ages (within a two-year range), genders, and academic interests.

For the opening workshop activity, Olly and Caroline directed everybody (the pupils and the research team) to sit in an oblong circle. In sequential order, each circle member was asked to state their name and generate a word describing their feelings about the future in order to uncover the group’s varying outlooks on life - optimists and pessimists, those curious and open-minded about future society and others with subversive ideas of their own. The activity itself was a useful way to introduce the members of the research team to the pupils and the pupils to each other. It felt like sitting in the oblong circle and giving every person an equal platform set the tone for the remainder of the session - many pupils had the confidence to speak aloud and share their thoughts, rather than passively observing Olly and Caroline as they might have done in a traditional teacher-centred style of lesson. Nevertheless, there were definitely some pupils who were more vocal than others - the difference in age between them appeared to interplay with individual confidence in publicising their opinions, at least initially.

Within our oblong circle, Olly and Caroline expertly shepherded the introductory sentiments into a group discourse around the future of society from local (Bristol), national, and global lenses. Olly and Caroline anchored the discussion, producing some conversation starters in the form of written future predictions they had brainstormed prior to the session. As an adjunct activity to the future mapping discussions being floated around our oblong circle, whenever a new future prediction was mooted, the author of the idea was asked to write it down on a post-it note and pin it to a chronologically labelled line of string which traversed the breadth of the classroom, known as ‘the timeline’. The pupils were then asked to move in physical space and stand at the place on the timeline which corresponded to the year they believed the prediction would become a reality (if at all). The timeline activity provided a temporal way for the participants to represent their ideas - mapping their predictions for world and personal events from the present day until the end of the current century. Not only was this a particularly effective way of engaging the pupils to envision their ideas, but it served as a visual representation of the mood in the room which we were able to reflect upon as a team following the workshops.

The pupils showed a particular interest in the notions of robotic bee pollinators and the Bristol veganism revolution but these ideas seemed to be rather polarising. Environmental sustainability, it seemed, could incite just as much discussion within the Generation Z as it does for their elders. Meanwhile, with regards to VR, the idea of replacing poor Mr Yarrow (the chief science technician who was our regular staff observer in the workshops) and members of school staff with VR teachers was a prediction that was universally panned. “It’s never going to happen,” said more than one pupil. This was a bit of a surprise for the research team “but you’d be able to study from the comfort of your own home”, Stu noted to one pupil. These attitudes towards VR cemented some of the concerns which have been mooted about the social impacts of the technology, and the pupils’ opinions perhaps betrayed the importance of the social interactions provided by traditional educational environments.

For researchers looking to run this activity for themselves, however, it did come with some minor caveats. As an accurate barometer (to be used as a research datapoint) for tallying opinions, it was unsuitable. For example, when asked to stand on the timeline to indicate when this would happen, it was difficult to infer any specific dates because there was not enough space for all the pupils to congregate together - instead, they mostly stood in a horizontal line. But, this was not really the point of the exercise in our particular project - we used it primarily to create a buzz about the workshops. Furthermore, although the timeline was an effective means of provoking energy and excitement in the room, at some points, this became counterproductive and some ideas verged on the facetious. For this activity, then, diligent management of the energy was essential and Olly and Caroline both did remarkably well at dialling back the overzeal when required in order to refocus the pupils towards still impassioned but more serious and meaningful conversations.

Another technique which Olly and Caroline deployed to great effect was the introduction of workshop journals, which were given to each pupil to use throughout the duration of the sessions. The individual and insular nature of this activity provided a potent counterweight to the vigour and thrills of the group interactions. In this first workshop, it was almost surreal to witness the dramatic de-escalation of intensity this exercise afforded following the timeline activity. The room filled with riotous discussion became eerily quiet, replaced with only the scratchings of furious pencil scribbling. The journal tasks were characterised by asking the pupils to reflect once more upon specific questions and ideas which had been posed by Olly and Caroline about the fictional future VR technologies during the workshops. One of the key motivations for this exercise was to afford an opportunity for the less vocal pupils to contribute without any social anxieties to overcome, particularly in early workshops. In later workshops, this rumination over ideas sometimes replaced the pupils personal perspective on matters with that of another character’s - another opportunity for role-play which may have given them licence to depict ideas without the fear of judgement attached to personal opinions.

As a researcher who is so often intent on providing innovative and engaging methods to elicit ideas from young people, Stuart conceded that it was “proof that more traditional educational activities and materials (i.e. paper journals and a pencil) should never be overlooked in the documentation of research”. The key to the effectiveness of this activity, however, was all about the timing. Throughout the following workshops, it was routinely deployed by Olly and Caroline following high energy moments. In many incidences it was most appropriate towards the end of the workshop sessions, offering the pupils the perfect antidote for their fictional design mania and enabling them to return to the status quo of their school day. Would the pupils have been as compliant towards journal writing before the “fun” of our innovative workshop methods? Probably not.

VR Workshop 2 - Experiencing VR First-Hand

One week later, we returned to the school heavily laden with Oculus Go Headsets. According to scientist and author Carl Sagan, “You have to know the past to understand the present“. With this in mind, the objective of this workshop was to educate the pupils upon the origins of VR and its rise to mainstream prominence. We also wanted to use this session to give the pupils a first-hand experience of using VR as not every member of the class had used the technology before.

The session began with a 10-minute group warm-up activity from Olly and Caroline, where the participants and researchers returned to the oblong circle arrangement and each person was asked in turn to speak briefly about an issue which had been particularly significant in the previous week’s session. Many of the pupils referred to one of the predictions which they had evaluated during the final activity of the previous week, though the answers generated didn’t seem to provoke too much analysis on this occasion. The pupils seemed keen to keep their answers brief before gesturing to the next person in the circle to provide their own answer. This was not necessarily surprising, as in a group setting, once the first person answers a question in a particular way, other people assimilate and respond in a similar pattern. Hence, it was Caroline’s role to probe the answers given by each participant for greater detail. It did feel, however, that putting the pupils on the spot to generate an answer in front of other group members was not the most comfortable format getting them to voice their personal opinions.

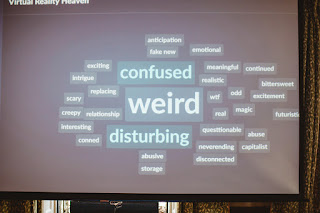

Following the recap upon the previous week, resident VR expert, Chris, provided the class with a 30 minute talk about the roots and emergence of VR. The pupils listened attentively as he shepherded them through the origins of VR to the present day. Chris’s gave the pupils a flavour for the key people and technical advances which have shaped today’s VR, and many of his cultural references seemed to hit the mark from the audience reaction - plenty of chortles and aha-moments at Ready Player One, the Matrix, Steve Jobs, Silicon Valley. The talk was an important means of grounding the current reality of where the technology is. 30 minutes did appear to be pushing the boundaries of some pupil’s concentration, however, and a longer lecture would likely have been detrimental. Following the talk, the pupils were given a chance to use the VR headsets to take ‘a walk in space’. They also answered pre and post evaluation questions about their feelings about VR. Meanwhile, the rest of the class built upon their journals with Olly and Caroline.

Time was becoming tight as the first group completed their VR experience - each group took around 10-15 minutes to complete the evaluations and the VR film. Hence, only 9 pupils were able to complete the experience and the final 3 had to be asked to undertake it the following week. The reactions of the pupils appeared to be positive as several stated that the experience had been “really good” immediately following the session. A couple of pupils expressed surprise during their experience, exclaiming “wow!”. We felt that more time would have been useful for them to properly experience VR in different contexts and, in turn, given them a firmer grounding for some of the ethical issues facing the technology. Then again with only three hour-long workshops, time was a scarce luxury.

VR Workshop 3 - Applying Our Knowledge of VR Ethics

Workshop 3 sought to build upon the learning of the previous workshop and rebalance the sessions towards further active participation from the pupils. The focus of the session was to bring together their wider visions of the future with their new knowledge of the VR technology, through a design-fiction style activity.

Following the now familiar refresher activity in the oblong circle, the participants were presented with a range of topics - law and order, the environment, health care, and history - upon which they would develop fictional VR design ideas. The pupils were given the opportunity to review the different topics before selecting the idea they wished to explore in collaboration with other participants with the same interest. In a series of intentionally brief brainstorming iterations, the groups began to elaborate on their ideas before each group then outlined their VR application to the wider class. The ideas presented included ‘Don’t Be Friends With Kasey’ (Law and Order) - using VR to educate young people about the dangers of knife crime from the perspectives of both victims and perpetrators; ‘Bucket List VR’ (Healthcare) - using VR to give hospital patients a chance to fulfil their dreams; ‘Space Trash Remover’ (Environment) - a robot controlled by scientists in VR which would collect man-made debris orbiting the earth; and ‘Lived History’ (History) - a VR experience that would allow users to undertake historical reenactments.

Sometimes presenting ideas can be an awkward and anxious affair for adults, let alone young people who may not necessarily know each other that well. But, Olly was able to use the power of role-playing to disarm any feelings of uneasiness experienced by the pupils by channelling the persona of a TV reporter, guiding the pupils’ explanations of their ideas with structured questions. The pupils seemed to buy into the fantasy and after the first group had been interviewed about their idea, there was palpable excitement as the remaining pupils prepared their own interview soundbites. When put to a democratic popularity vote, two winning ideas emerged - Don’t Be Friends With Kasey and Bucket List VR. These groups were asked to role-play hosting a press conference about their ideas, with the other members of the class playing the role of journalists asking them questions. This gave us the opportunity to ideate the most credible ideas in greater detail without alienating the other class members.

From the perspective of the University of Bristol researchers, Stu and Chris, it was the first and third workshops which engendered the greatest personal introspection. Although in these workshops Stu and Chris contributed the least to proceedings, these sessions gave them the opportunity to observe Olly and Caroline as they applied their immersive theatre skills and creative exercises in practice. They learned about how to carefully manage energy in the room in order to foster different types of communication, how to quickly build trust with participants, and (if all else fails) how to “vibe it” - Caroline’s colloquialism for adapting to events and ideas and improvising responses.

Sadly, the workshops focusing on VR were all too fleeting, constrained by the time resources permitted to us by the school and the duality of investigating the ethics of VR and Quantum in parallel. Notwithstanding, the conversations which took place were of great value to all parties. We met our objectives of learning about young people’s understanding and views of VR ethics (albeit in a specific context) to form part of our rich tapestry of research on the topic, developed ideas to inform our production on VR ethics, furthered the pupils’ understanding of the history of the technology, and created a climate for establishing diverse and unique bonds between our participants which we hope they have continued to cement following the completion of the project.

We would like to thank the members of the VR team at the Centre for Innovation and Entrepreneurship, Jo Gildersleve and Professor Kirsten Cater, without whom the sessions at the school would not have been possible. We’d also like to give our thanks to Redland Green - particularly Jenna Bush and Ian Yarrow for helping us with the organisation and running of the sessions. And, of course, we must thank the pupils we worked with - their spirit was remarkable and they made this project a true pleasure to undertake.

Comments

Post a Comment