Step 9: Create Some Conflict

The process of translating a germ of an idea into a performable script is one of my favourite parts of the knowledge transfer secondment.

As before, with this process we have tried to follow an iterative pattern to allow our researchers to remain engaged with this creative metamorphosis at every step of the way.

That said, it's amazing how much work you do when you are asleep, or driving on the motorway or jogging down the tow-path & ideas leap forward without you even realising it. That's why we keep sharing.

Firstly we share an idea - maybe even just pinpoint the one thing that we want to explore more. Next, with researcher buy-in, we flesh it out a bit to a 'treatment' with characters, situation & some sense of narrative arc. That bit can take quite a while without much seeming to happen. It's the magical alchemy moment you hope. For Kilter, its often walking in a field & turning the idea over and over.

Once the researchers have approved the treatment, we begin writing. First we create the world - is it in the future? (yes, for VR), is it in a parallel universe? (yes, for quantum). Then we create the characters. It's a cliche but you do need to understand a character's background & motivation before you can write a compelling line of dialogue. We find out where they went to school, what their relationship is like with their parents.... & then we sit down & it spills out: a rehearsal draft.

We go back into our researchers, we clear our throats... & we put on funny voices. At that moment something transformational happens. Until we start 'acting' -however ropey that might be at this stage in proceedings - it has all been theoretical. Something special happens when we ply our trade & introduce believable new people into the room, from strange far-fetched futures with strange far-fetched opinions & motivations. You feel the researchers edging forward on their seats & wondering who they can invite to see this thing....

At each stage in the forging of the script we share what we have with our academic partners & invite them to contribute three things.

1. Firstly, partly to protect ourselves but also to point out the inherent positivity behind creativity, we ask for what they love. What, at all costs, we should keep. This inevitably has a few surprises. Rarely it is a critical plot point or a finely shaped character observation. More often it is a dodgy accent or an accidental joke we played with scientific language.

2. Secondly, we ask for questions. What did you not understand? Hopefully, we can solve these problems together. Sometimes its something scientific but as often as not its something to do with a character's motivation.

3. Constructive criticisms please. We hold our breath. Its at this stage of proceedings that I remember how creative everybody is. We are in the room as the artists, but most educated people seem to be very well versed with complicated science-fiction plot-lines. We come away cowed because the researchers have nailed some vital element in the performance & we still can't tell the difference between 'super-position' & 'entanglement'.

Central ideas for both our performed pieces came directly from the researchers. We are really keen always to label that as clearly as possible. We don't want to be helicopter artists who look at things from our perspective & then go away to create our reaction. We want it to come from the researchers.

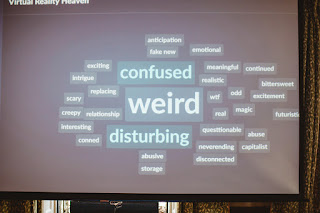

Better still for our VR performance, many of the ideas came from the young people we worked with in Redland Green school. They talked about a 100 year old, dying at their birthday party & that became our central premise. They imagined a VR company called 'Bucket List' that fulfilled your dreams before you died. We had BucketList t-shirts printed up & a whole world of corporate hocus-pocus to frame our imaginary VR application.

For each of the scripts we have created, there has been reams of different positives & constructive criticisms but there are a few universal questions:

1. Does it make us look bad? During this project we were keen to uphold our ethical values at all stages of the process. For this reason, participant diversity and sensitivity to participant beliefs, values, and circumstances, were prioritised. Quantum researchers helped us carefully articulate a programme note which explains that this FICTIONAL FANTASY could not happen in real life, under real circumstances with real researchers.

2. Does it have to be so pessimistic? It's true Kilter does love an apocalypse but we don't actually always dive straight into the worst-case scenario. On the contrary we draw on camp fear's worst visions of the future in order to generate conflict within the performance. A play has to have play. A drama needs drama. We can't have everyone agreeing with each other. In fact, if we want the audience writhing in their seats, changing their allegiances & coming out with a 100s of questions on the tips of their tongues, we can't even agree with ourselves. We have to create a murky whirlpool of ideas that makes sense to different people in different lights on different days. As Tom Stoppard once observed "writing dialogue is the only socially acceptable way of completely disagreeing with yourself".

Comments

Post a Comment